Strictly speaking, an animal or human is never alone. Living beings are populated by many billions of microorganisms, which live both in and on these bodies. As is demonstrated by the gut microbiome, such microorganisms can play vital roles. And they also do so for plants. Most endophytes, as these microorganisms that populate plants are called, hardly affect their hosts. The few that do, however, don’t hold back. They bind nitrogen from the air or release phosphate that was stored in the soil so that it becomes available to plants again. Some microorganisms protect their hosts from disease. And where tomatoes or strawberries are concerned, their taste changes according to the single-cell organisms that live on them.

Endophytes have been Birgit Mitter’s specialty for a long time. The microbiologist worked for the AIT Austrian Institute of Technology for many years, engaging in molecular-biological analyses of microorganisms in and on plants in numerous projects. In the course of this research, which included two projects funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), Mitter and her colleagues found themselves looking for ways to introduce bacteria to seeds in an efficient way in order to be able to then look into the interactions between the plants and the microbiome. Managing to do exactly that eventually led to the spin-off Ensemo, based in Tulln in Lower Austria, which Mitter co-heads with her former AIT colleague Nikolaus Pfaffenbichler.

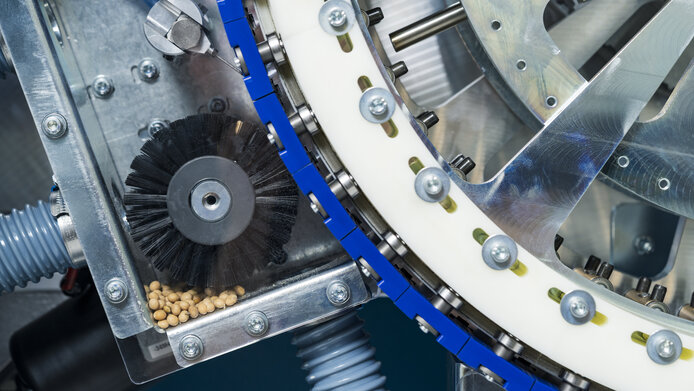

Ensemo provided a stage to develop a technology invented as part of basic research up to the point where it was ready to be marketed: a machine that rapidly injects microorganisms into many thousands of plant seeds is also the key to supporting crop plants in a controlled way without having to rely on chemical means that potentially harm the environment. The targeted use of the interaction between microbiome and plants could potentially simplify organic agriculture, making a sustainable way of cultivating fields more competitive.

Reducing fertilizers and pesticides for economic reasons

The first products have already been launched. They include soy seeds enriched with rhizobia, which are bacteria that fix nitrogen from the air and make it available to the plants. “As a result, there’s almost no need for additional nitrogen-based fertilizers,” Mitter says. “In general, being able to save on fertilizer and pesticide, huge amounts of which are spread across our fields today, turned out to be a strong economic argument in favor of our technology.” Ensemo staff are already testing further microorganisms, for instance ones that mobilize phosphorus, as well as hormone-like substances that could potentially increase plant resilience.

![[Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/1/e/csm_TeamGrabungVelia_cVerenaGassner_3d365837fc.jpg)

![[Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/6/d/csm_MagdalenaHauser_WolfgangLechner_CorporateRetreat_cParityQC_e8b6874984.jpg)

![[Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/_processed_/f/d/csm_AITHYRA_GeorgWinter_cOEAW_DanielHinterramskogler_f47355b43d.jpg)